The conflict between the Kerala government and the Union over state borrowing limits has brought attention to the complexities of fiscal federalism in India. The Kerala government filed a suit in the Supreme Court, challenging the Union’s control over state debts under Article 131. This legal battle focuses on Article 293 of the Indian Constitution, which regulates state borrowing. As Kerala seeks more autonomy, the Union emphasizes macroeconomic stability. This case highlights the need for constitutional clarity and potential amendments to balance state autonomy and national financial stability.

Origin of the Article

This editorial is based on “State Debt and the Constitution,” published in Economic and Political Weekly on 22/06/2024. The article highlights a legal dispute between Kerala and the Union over financial control, suggesting the need for constitutional amendments.

Relevancy for UPSC Students

Understanding this topic is crucial for UPSC aspirants as it aligns with GS Paper 3, covering fiscal policy, government interventions, and resource mobilization. It provides insights into the constitutional provisions affecting state borrowing, essential for topics on fiscal federalism and economic governance. Familiarity with these issues will aid in answering questions related to state finances and economic policies in both prelims and mains examinations.

Why in News

The Kerala government’s recent legal battle against the Union over borrowing limits under Article 131 of the Constitution has thrust Article 293 into the spotlight, highlighting potential constitutional amendments. This issue is crucial for UPSC aspirants as it connects with the principles of fiscal federalism and the evolving dynamics of state borrowing, previously addressed in UPSC questions on fiscal responsibility and budget management.

Provisions and Limitations of Article 293 of the Indian Constitution

Provisions

State Borrowing Power: Article 293 of the Indian Constitution grants states the authority to borrow within India, secured by their Consolidated Fund. This borrowing must align with the limits set by the state legislature, ensuring that states have the autonomy to manage their finances while adhering to constitutional constraints.

Union Guarantees: The Union government can provide guarantees for state loans, but these guarantees are subject to limits established by Parliament. This provision balances state autonomy with the need for fiscal oversight and stability at the national level.

Consent Requirement: If a state owes any outstanding loan to the Union or a loan guaranteed by the Union, it must seek the Union’s consent before raising any new loan. This ensures that states cannot overextend themselves financially, protecting both the state’s and the Union’s fiscal health.

Temporary Overdrafts: States do not need Union consent for temporary overdrafts or similar arrangements with the Reserve Bank of India. This provision allows states some flexibility in managing short-term financial needs without bureaucratic delays.

Continuation of Previous Loans: Loans that were outstanding at the commencement of the Constitution continue to be governed by the same terms and conditions. This ensures a smooth transition and continuity in financial obligations for states.

Limitations

Union Debt Requirement: Article 293’s regulatory authority is contingent upon states owing money to the Union. If a state clears its Union debts, the article lacks provisions for regulating future borrowing, potentially creating a constitutional gap.

Potential Constitutional Gap: Economically stronger states could clear their Union debts and then borrow without Union oversight, exploiting this gap. This could lead to a lack of uniformity in fiscal discipline across states.

PSU Loophole: States often use Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) to bypass Article 293 restrictions, leading to fiscal opacity. This practice complicates accurate assessment of state indebtedness and poses hidden financial risks, undermining overall fiscal transparency and accountability.

Key Questions for the Constitution Bench

State’s Right to Borrow: The recent Kerala vs. Union government case raises critical questions about whether states have an inherent right to borrow under Article 293 and the extent of the Union’s regulatory powers. This issue is central to defining the balance between state autonomy and national fiscal stability.

PSUs Debts: Another key question is whether debts raised by state government PSUs fall within the scope of Article 293. Clarifying this will address the loophole that allows states to bypass borrowing restrictions, ensuring greater fiscal transparency and accountability.

Latest Trends in State Borrowing from the Union

Decrease in Union Loans: There has been a significant decline in the Union’s share of state loans, from 57% in 1991 to just 3% in FY 2020. This trend indicates states’ increasing reliance on market borrowings and other financial sources, reflecting a shift towards greater financial independence.

Pandemic Impact: The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily increased state borrowing from the Union, rising from 3% in FY 2020 to 8.6% in FY 2024 due to economic pressures. However, this is expected to be a short-term trend, with states likely reverting to pre-pandemic borrowing patterns as the economy recovers.

Arguments in Favour and Against State’s Uninterrupted Right to Borrow

Arguments in Favor

Fiscal Autonomy: Borrowing empowers states to manage their finances independently, facilitating the funding of development projects and meeting local needs without over-relying on Union grants. This autonomy aligns with the principles of federalism and fosters a sense of self-reliance.

Economic Development: State borrowing can finance large-scale infrastructure projects, stimulating economic growth. By bridging temporary revenue shortfalls, it helps maintain continuity in essential services and development programs, attracts private investments, and forges public-private partnerships.

Flexibility in Financial Management: Borrowing provides a buffer against economic shocks and revenue fluctuations, enhancing financial resilience. It also offers an alternative to increasing taxes during economic stress, which may be politically and economically challenging.

Accountability to the Local Electorate: The power to borrow makes state governments directly accountable to their constituents, as they must justify their borrowing decisions and demonstrate effective use of funds, leading to more informed electoral choices.

Competitive Federalism: Borrowing enables states to compete by attracting investments and businesses and fostering innovative development strategies. This competitive federalism can lead to the spread of best practices across states and contribute to overall national development.

PESTEL Analysis

| Political: The central issue is the interpretation of Article 293, where Kerala seeks judicial review to assert its borrowing autonomy against Union constraints. The Supreme Court’s involvement underscores the high-stakes political nature of federal relationships and state rights. Economic: The dispute impacts economic stability and fiscal policy across India. Kerala’s plea for removing borrowing ceilings highlights tensions between state-led economic initiatives and national budgetary oversight. The economic recovery post-COVID-19 also influences the dynamics of state and Union borrowing practices. Social: The case reflects broader social implications, such as the accountability of state governments to their constituents. Increased fiscal autonomy could enable better local governance and direct responses to social needs. Technological: Recommendations for using AI and blockchain for fiscal monitoring point to an evolving approach where technology could be critical in ensuring transparency and efficiency in state borrowing processes. Environmental: Not directly impacted by the borrowing dispute, though fiscal policies enabled by borrowing autonomy could affect state-level environmental initiatives. Legal: The legal framework, primarily Article 293 and its interpretation, is central to this dispute. The Supreme Court’s decision will set a precedent for how state borrowing limits are enforced and interpreted in relation to Union oversight. |

Arguments Against

Risk of Fiscal Indiscipline: Unrestricted borrowing power may lead states to accumulate unsustainable debt levels, jeopardizing their long-term fiscal health. Political considerations might override economic prudence, resulting in resource misallocation.

Macroeconomic Stability Concerns: Excessive state borrowing can interfere with national monetary and fiscal policies, complicating economic management at the Union level and potentially impacting the country’s credit rating and borrowing costs.

Inter-State Disparities: Varying economic strengths of states can lead to significant differences in borrowing capacities, exacerbating regional inequalities. Economically stronger states may secure loans on favorable terms, while poorer states face higher borrowing costs.

Complexity in Debt Management: Independent state borrowings complicate overall public debt management, requiring sophisticated oversight mechanisms. Overlapping debt obligations between states and the Union could create legal and financial complexities.

Potential for Default and Bailouts: States facing severe financial distress might default on loans, with far-reaching consequences for creditors and the financial system. There’s often an implicit expectation of Union bailouts, creating a moral hazard that could encourage irresponsible borrowing.

Other Federal Systems of Managing Subnational Debts

Brazil: Brazil’s Fiscal Responsibility Law imposes strict borrowing limits on all levels of government, ensuring fiscal discipline. This framework helps maintain financial stability and prevent excessive debt accumulation.

United States: US states have high autonomy in borrowing but are subject to market discipline. This balance of independence and financial accountability ensures prudent fiscal management.

Germany: Germany’s cooperative federalism model involves shared fiscal responsibility between federal and state governments, ensuring coordinated and balanced financial management. This approach fosters fiscal discipline and stability across all levels of government.

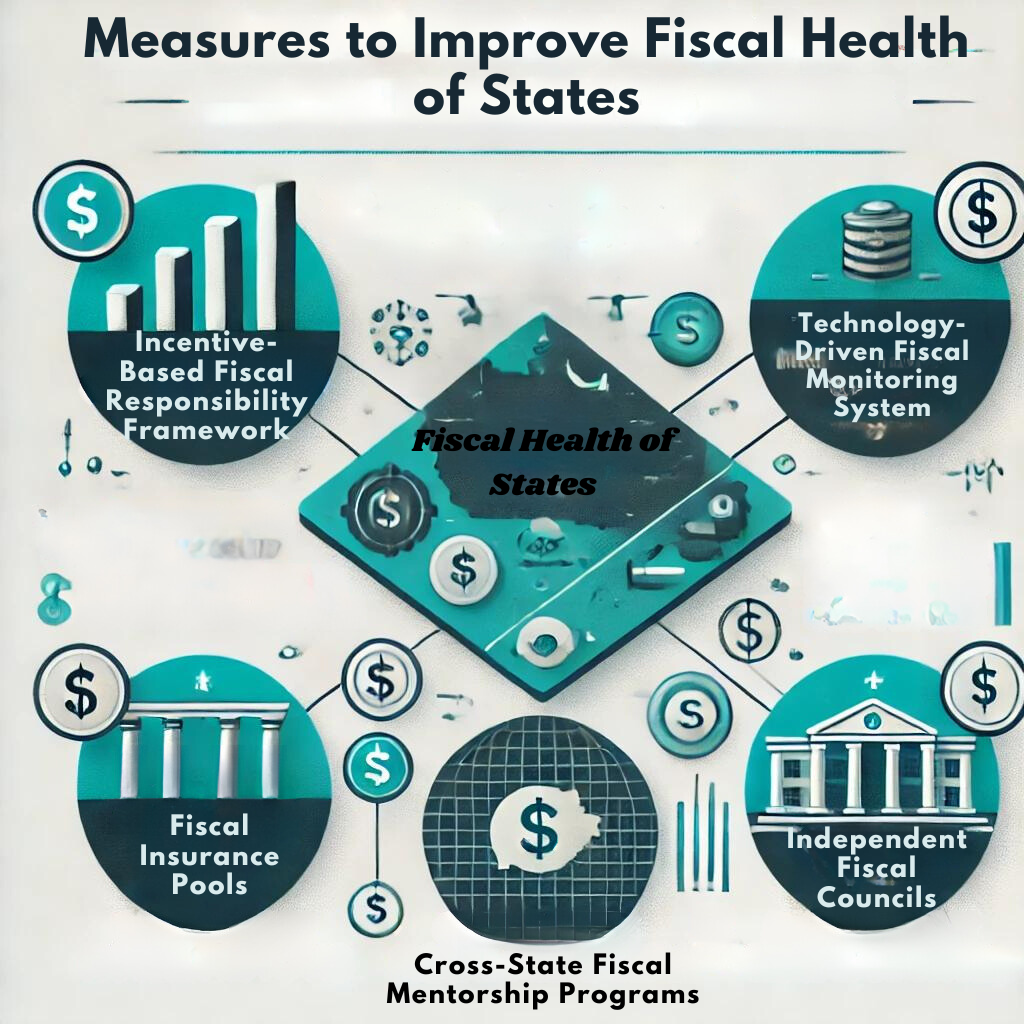

Measures to Improve Fiscal Health of States

Incentive-Based Fiscal Responsibility Framework: Implementing a tiered system of borrowing limits based on fiscal performance metrics would encourage states to improve their fiscal management. This system would create a positive feedback loop, promoting continuous fiscal discipline.

Technology-Driven Fiscal Monitoring System: Developing a real-time, AI-powered fiscal monitoring system using blockchain technology would enhance transparency and provide early warnings of fiscal stress, ensuring timely interventions.

Fiscal Insurance Pools: States could contribute to a collective insurance fund based on their fiscal health, providing temporary relief during economic shocks. This system would incentivize fiscal prudence and reduce the need for excessive borrowing.

Cross-State Fiscal Mentorship Programs: Pairing fiscally stronger states with weaker ones in mentorship programs would foster inter-state cooperation and spread best practices, improving overall fiscal health.

Independent Fiscal Councils: Establishing non-partisan fiscal councils at the state level would provide objective assessments of fiscal health and offer recommendations for sustainable debt management, enhancing fiscal stability.

Conclusion

The ongoing debate over fiscal federalism underscores the need for a balanced approach to state borrowing and financial autonomy. As we await the Supreme Court’s verdict, policymakers must consider reforms that promote fiscal discipline while empowering states. This delicate balance will enhance the overall economic stability of India, fostering sustainable growth and inclusive development.

| UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs) Mains Q. The concept of cooperative federalism has been increasingly emphasized in recent years. Highlight the drawbacks in the existing structure and the extent to which cooperative federalism would answer the shortcomings. (GS-II, 2015) Q. Discuss the provisions and limitations of Article 293 of the Indian Constitution. How does it impact the fiscal autonomy of states in India? |