Introduction

In 2014, the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act was introduced with a promise to protect and empower the ubiquitous street vendors populating India’s bustling cities. As we mark the tenth anniversary of this Act, it becomes crucial to evaluate its effectiveness and the numerous obstacles that hinder its full potential. This editorial delves into these multidimensional challenges, aiming to shed light on the practical difficulties street vendors face despite the legal backing intended to support them.

Origin of the Article

This editorial draws on insights from “Implementing the Street Vendors Act,” published in The Hindu on May 1, 2024. The article explores the Act’s ambitions and the reality of its enforcement.

Relevancy for UPSC Students

Understanding the Street Vendors Act is vital for UPSC candidates, highlighting governance, policy implementation, and urban development—key topics in the civil services exam. It offers insights into administrative challenges and the role of local bodies, directly correlating with the Indian Polity and Governance segment of the syllabus.

Understanding Street Vendors and their Associated Rights?

Street vendors are ubiquitous figures in urban landscapes, often seen selling goods from temporary setups along busy streets. These vendors might set up shop on pavements or roam the city with their wares in carts or baskets, bringing everyday essentials right to the doorstep of the urban populace. This form of trading, while lacking a permanent retail space, is an integral part of the economy, especially in bustling city centers.

The population of street vendors has seen a dramatic rise globally, with significant numbers in cities across Asia, Latin America, and Africa. In India alone, close to 50 lakh street vendors have been officially recognized, showcasing a substantial presence that varies widely across regions—from a high of 8 lakh in Uttar Pradesh to a modest 72k in Delhi. Interestingly, no street vendors have been identified in Sikkim.

Legally, the right to trade, as enshrined in Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution, supports these vendors by granting them the fundamental right to practice their trade. This constitutional backing is crucial as it legitimizes their vocation and provides a legal framework to protect their livelihoods.

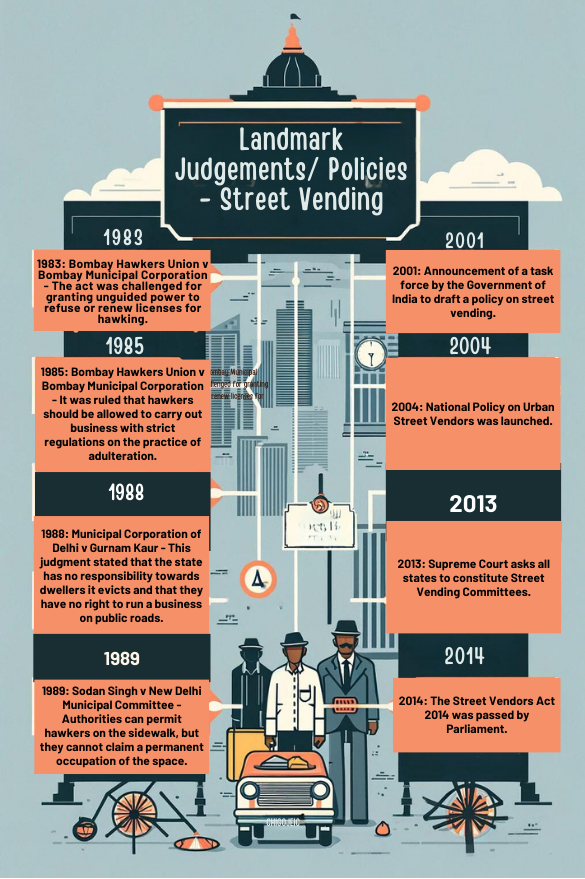

Landmark Judgements and Policies on Street Vending

- 1983: Bombay Hawkers Union v Bombay Municipal Corporation – The act was challenged for granting unguided power to refuse or renew licenses for hawking.

- 1985: Bombay Hawkers Union v Bombay Municipal Corporation – It was ruled that hawkers should be allowed to carry out business with strict regulations on the practice of adulteration.

- 1988: Municipal Corporation of Delhi v Gurnam Kaur – This judgment stated that the state has no responsibility towards dwellers it evicts and that they have no right to run a business on public roads.

- 1989: Sodan Singh v New Delhi Municipal Committee – Authorities can permit hawkers on the sidewalk, but they cannot claim a permanent occupation of the space.

- 2001: Announcement of a task force by the Government of India to draft a policy on street vending.

- 2004: National Policy on Urban Street Vendors was launched.

- 2013: Supreme Court asks all states to constitute Street Vending Committees.

- 2014: The Street Vendors Act 2014 was passed by Parliament.

Understanding the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014, was enacted with a pivotal goal: to legalise and regulate the bustling world of street vending in urban areas across India. This legislation is foundational in safeguarding the rights of street vendors, ensuring their trade is recognised and protected under the law.

Legal Framework and Implementation

The Act tasks state governments and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) with crafting by-laws, executing plans, and managing the street vending activities efficiently. This involves a structured approach to urban planning and vendor management to maintain order and accessibility in public spaces.

Roles and Responsibilities

A key feature of the Act is the establishment of Town Vending Committees (TVCs). These committees are unique participatory bodies where 40% of the members are street vendors themselves, with women vendors representing at least a third of this group. The TVCs are instrumental in integrating vendors into designated vending zones, issuing Vending Certificates (VCs), and handling any grievances through a Grievance Redressal Committee headed by a judicial figure.

Regular Surveys

To keep the data on street vendors current and accurate, the Act mandates that states and ULBs conduct comprehensive surveys every five years. This helps in understanding the evolving dynamics of street vending and ensuring that policies remain relevant and effective.

Significance of Street Vendors in India

Street vendors are more than just sellers; they are vital cogs in the urban economic wheel, providing livelihoods for millions, particularly the migrant and urban poor populations. Their stalls not only offer a variety of goods and services, making daily necessities accessible and affordable, but they also preserve and promote the rich culinary and cultural heritage of India.

Government Initiatives to Support Street Vendors

To further bolster the support for street vendors, the government has launched several initiatives:

- PM SVANidhi Scheme: Provides micro-loans to vendors to help them sustain and grow their businesses.

- National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM): Focuses on enhancing the employability and earning potential of the urban poor, including street vendors, through skill development and access to credit.

- Urban Street Vendors Component under DAY-NULM: Aims to improve the infrastructure for vending, organize vendors into Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and facilitate their integration into formal urban economies.

Through these comprehensive measures, the Street Vendors Act not only legalizes but actively promotes a more structured and supportive environment for street vendors across India, aligning with broader urban development and poverty alleviation goals.

Challenges and Solutions for Street Vendors in India

Persistent Challenges in Implementation

Despite legal protections under the Street Vendors Act, many vendors face continued harassment and evictions, often because of lingering outdated views that see them as nuisances rather than legitimate business operators. A lack of awareness about the Act’s protections among vendors, the public, and even within state authorities exacerbates these issues. Additionally, representation in Town Vending Committees (TVCs) is frequently inadequate, with women vendors particularly underrepresented and marginalized.

Governance and Societal Barriers

Urban governance mechanisms often fail to integrate street vendor needs into broader city planning agendas, such as those outlined in the Smart Cities Mission, which prioritizes infrastructural over social considerations. This oversight can foster an exclusionary development model that sees street vendors as obstructions to urban aesthetics rather than as contributors to the urban economy. Moreover, societal biases persist, with vendors often viewed negatively in the vision of a high-tech urban future. These challenges are compounded by new pressures from climate change and the rise of e-commerce, which threaten traditional vending practices.

Improving Vendor Conditions: Strategies for Enhancement

To counter these challenges and improve the conditions of street vendors, several strategies can be implemented:

- Strengthen Implementation: Improve the identification of vendors and raise awareness of their rights and available supports through educational workshops and collaborations with NGOs. Ensuring that all vendors, especially the newly recognized, understand their rights and the resources available to them is vital.

- Expand Benefits: Offer more comprehensive benefits, including accident relief, compensation for natural death, educational support for their children, and pensions in crises. These benefits would provide a safety net that supports both the vendors and their families.

- Prevent Harassment: Stronger enforcement of laws to protect vendors from arbitrary evictions, confiscation of goods, or unjust fines is essential. Such protections are fundamental to ensuring vendors can operate without fear of losing their livelihoods.

- Enhance Representation: Ensure vendors, particularly women, have meaningful representation in decision-making processes. Effective participation in TVCs can lead to more equitable policies and better advocacy for vendors’ needs.

- Promote Financial Inclusion: Encourage inclusion of street vendors in the formal financial system, providing them access to credit, savings, and insurance. Partnerships with microfinance institutions, support from self-help groups, and adoption of digital banking solutions can empower vendors economically and help stabilize their operations.

Conclusion

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014, marks a significant legislative effort to recognize and regulate the vital role of street vendors in India’s urban tapestry. However, to realize the full potential of this Act, ongoing challenges must be addressed through robust implementation, enhanced protections, and inclusive governance. Strengthening the framework supporting street vendors will not only safeguard their livelihoods but also enrich the urban economies they sustain. As we look forward, it is crucial that policy adjustments and community engagement evolve in tandem to ensure that street vending is not just tolerated but valued as a vibrant part of our urban culture and economy.